From the Saturday, Nov. 23, editions of The Daily Journal (Kankakee, Ill.) and The Times (Ottawa, Ill.) …

From the Saturday, Nov. 23, editions of The Daily Journal (Kankakee, Ill.) and The Times (Ottawa, Ill.) …

By Dave Wischnowsky

The WISCH LIST

Everybody is interested in money.

But who knew that money is also so interesting?

Thanks to Chicago’s Money Museum – yes, that’s a real place – I I’ve learned that, with interest. And as an added financial bonus, I’m also now one of the few guys this side of Scrooge McDuck who can tell you what a million bucks in one-dollar bills looks like.

It looks good, by the way.

Last week, I popped in to of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (230 S. LaSalle St.) in the Loop’s financial district, hoping to make greater sense of money by touring the museum located inside.

Upon my arrival in the lobby, I was greeted by a chummy security guard who seemed exorbitantly pleased to see me, before saying, “A lot of people don’t know this museum exists,” which explained why.

“Although, we do get a lot of student field trips,” he added before explaining how I’d need to show a form of ID and step through a scanner much like the ones at O’Hare before I could gain entrance.

After emptying my pockets – but keeping my shoes on – I slipped through the scanner with no waiting (unlike O’Hare) and at no cost stepped into a space filled with more money than I’ve ever seen in my life.

Or probably ever will.

Come Dec. 23, the Chicago Fed will celebrate its 100th birthday, marking the occasion when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve System into law with the stroke of his pen.

The Chicago branch is one of 12 regional Reserve Banks, along with the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., that make up the nation’s central bank. And each day in the Windy City, the Fed shreds about $23 million in worn out bills, ships $169 million to financial institutions throughout the district and handles more than $146 billion – that’s with a “b” – in financial transactions.

Of that enormous number, only about $213 million of the transactions are in cash, while $7.2 billion are via check. The rest – a scant $139 billion – is conducted electronically.

Each weekday, the museum offers guided tours at 1 p.m. or self-guided ones anytime between 8:30 a.m. and 5 p.m. It does a great job of telling the history of the Fed and dropping interesting facts about what was actually the nation’s third attempt at a central bank after the first two flopped.

From its beginning, the Chicago Fed kept meticulous records, some of which are displayed in logbook that lists the salaries of its original 41 employees. In 1913, James B. McDouglas, the bank’s first Governor (later re-titled to “president”), earned an annual income of $20,000. Meanwhile, Harold Burns, the bellboy, earned $286.

Between 1918 and 1922, the Chicago Fed constructed its current building on LaSalle Street, which the bank’s 1920 annual report described as “simple in outline and severely plain in its general effect.”

The museum’s contents not, however, with intriguing artifacts such as a $5,000 bill from 1934 and a $1 silver certificate from 1891. Another display teaches you how to spot counterfeit bills. Nearby, a noisy roller coaster of a contraption shows the life cycle of cash.

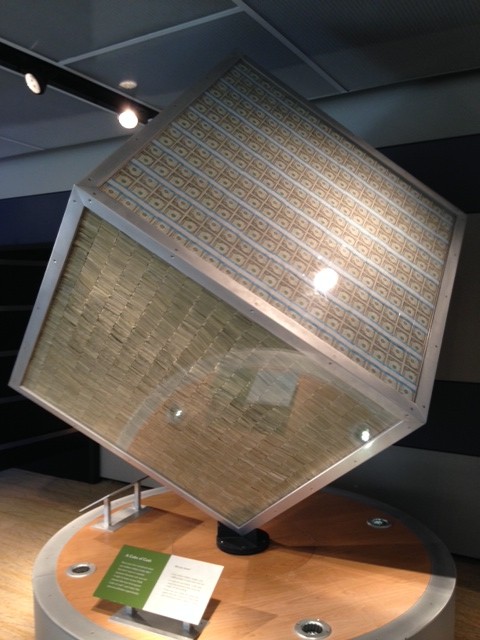

The museum’s stars, however, are its three separate collections of $1 million bucks.

The first – a million in singles – is displayed in a four-foot-square cube that weighs more than a ton. The second is a pile of twenties in $2,000 packs covered by a plastic bubble. And the third is a briefcase filled with $100s that you can stand beside and get a free photo taken.

No matter how you pose, there’s one guarantee: you’ll look like a million bucks.